Science Needs Identified by Idahoans

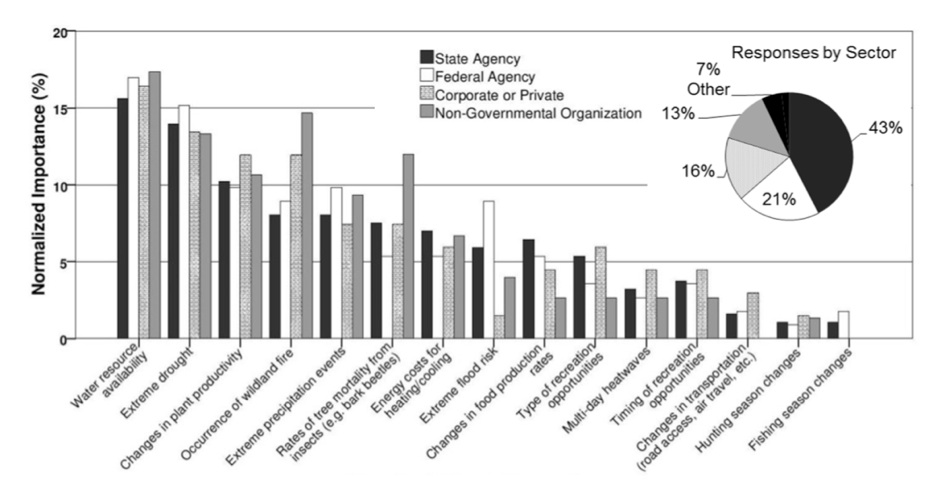

FIG. 2: Perceived importance of climate change impacts in Idaho (United States) by end users. Responses (n 5 440) are stratified by sector of the respondent: state agency, federal agency, corporate or private, or nongovernmental organization (with the ‘‘other’’ category removed due to small sample size). The response rates of each sector are shown top right. ‘‘Normalized importance’’ is the number of times an impact was selected by an individual end user divided by the total number of selections within a sector.

Survey methods

Given the calls in the literature to engage stake- holders and end users in identifying science needs, our first step was to solicit input from individuals affiliated with some aspect of natural resource management in Idaho. Many of the proposed solutions are time and resource intensive, such as establishing boundary orga- nizations or structured knowledge networks. In this paper, we adopted a relatively inexpensive, efficient approach to enhancing the connection between science and end users through the use of an online survey of key informants in Idaho. McKenna and Main (2013) articulate the value of using key informants to obtain expert information related to a community’s needs; one recent example can be found in Berndtson et al. (2007), where researchers developed lists of potential study participants from staff recommendations, the literature, and snowball sampling to help identify grand challenges in public health.

An online survey was administered in February 2012 to evaluate which climate indicators were of primary concern to end users and which indicator datasets would be the most useful in their jobs (see the supplemental material, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/WCAS- D-13-00070.s1, for a copy of the survey). Using a pur- poseful (Coyne 1997) and snowball sampling approach (Creswell 2009), we obtained participant contact information from agency and organizational websites, and asked survey participants to provide contact information for other potential participants, or to forward the online survey directly to their colleagues. Ritchie et al. (2003) recommend purposive sampling as appropriate when the sample is intended to represent individuals who meet key selection criteria, and they note that this approach helps ensure that all key groups are included. We specifically sought individuals who would be in a position to comment on the utility of climate science to management or policy decisions. Additionally, our selection criteria were attentive to covering the full suite of professions (natural resource managers, specialists, and community leaders) that would ultimately use the final products of this indicator-based assessment in their work, in a form of maximum variation sampling (Sandelowski 1995). Thus, our sampling approach is most appropriately characterized as what Patton (1990) calls stratified purposeful sampling, designed to achieve coverage of all groups. A total of 612 individuals were asked to participate. Participants included individuals working for state agencies (37%), federal agencies (32%), nongovernmental organizations (21%), and other entities (8%, corporate or private, and local governments).

The Internet survey was developed online using Qualtrics software and followed a modified Dillman method (Dillman et al. 2009), where participants were invited to participate through a work e-mail address and two weeks later received a reminder e-mail. The survey format included sequential questions about 1) perceived importance of climate change impacts within the state with a focus on natural hazards and social change and 2) indicators of climate change most desired for assessment within five designated systems: water, forest, rangeland, agricultural, and social systems. The survey first asked participants about their personal concern regarding a broad range of climate impacts, and then asked about relevance of climate data to their jobs in an attempt to avoid an order effect, which could have caused participants to answer all questions with respect to their work interests and induce undesired priming (Salancik 1984). Within the first part of the survey, all respondents were asked to choose up to five impacts they were personally concerned about from a broad set of possibilities (see supplemental material). The specific options within this broad set were designed to be far reaching in scope, but may have inadvertently primed the participants to focus their future answers only within the constructs of the impact options provided. Next they were asked to choose up to three responses (of the 12 possible, with three additional open-ended options) regarding direct measures of climate (i.e., direct temperature and precipitation metrics) they found most relevant to their job. They were then asked to choose one of the five designated systems (i.e., water, forest, rangeland, agricultural, social) that was most relevant to their job. This choice took them to one of the five possible subpages (one per designated system) where they could choose the top three indicators of the 12 or more options within that system. They were then asked if another one of the five

designated systems was relevant to their job. If so, they were then directed to that designated system’s subpage to again choose their top three most relevant indicators. After two (at most) designated system subpages the participants were then directed to the conclusion of the survey. The decision to limit respondents to no more than two systems was based on a need to minimize the burden on respondents, as the lists of indicators were quite long and because—given the breadth of respondents—we recognized that not all systems would be primarily important to all respondents.

We developed the survey questions collaboratively as a research group, with each discipline represented (e.g., hydrology, ecology, etc.), generating a comprehensive list of climate measures, potential impacts, and indicators that were considered most salient to each system and reflected the focus of similar work in other regions (Pederson et al. 2010; Betts 2011; USGCRP 2011a,b, 2012).

Summary of survey findings

A total of 100 surveys were completed, with respondent demographics mirroring those in the total population surveyed (Fig. 2). The top four concerns regarding climate change impacts were water resource availability (16% of respondents), extreme drought (14%), changes in plant productivity (14%), and wildland fire (10%; Fig. 2). Regardless of participant sector, concerns about biophysical impacts were consistently rated as the highest importance, and concerns about recreation and transportation impacts were rated as the lowest importance.

Based on a metric of ‘‘normalized importance,’’ which is defined as the number of times an indicator was selected by an individual end user divided by the total number of selections within a system, participants identified precipitation indicators as being the top three most useful climate measures: annual rainfall versus snowfall (23%), seasonality trends (22%), and general precipitation (14%; Fig. 3). Of all responses, 43% represented water-related occupational specialties as indicated by the choice of system specialties (Fig. 3). The top indicators for end users who selected the water resources system were streamflow timing, annual volumetric stream discharge, and stream baseflow discharge. Participants who selected the forest system focused on wildland fire severity and vegetation/wildlife distributions. Rangeland participants focused on vegetation indicators (i.e., plant productivity, vegetation distribution, and plant phenology). Agricultural participants focused on precipitation patterns, drought characteristics, and growing season length as their top priorities. Participants working with social systems selected water-based recreation, timing of peak visitation, and recreation restrictions due to wildland fire as the top climate change– related indicators.

Overall, participants were most concerned with water- related impacts resulting from climate change and considered information about water resources availability to be the most important measures of climate change that were relevant and useful for their needs (Fig. 2). The topics of fire and vegetation were also top areas of participant interest. The occurrence and impacts of wildland fire ranked fourth for participant concern (Fig. 2), and indicators related to fire were among the top four most relevant in forest, rangeland, and social systems (Fig. 3). The impact of climate change on plant productivity and growth rates ranked third for participant concern overall (Fig. 2).

Given the calls in the literature to engage stake- holders and end users in identifying science needs, our first step was to solicit input from individuals affiliated with some aspect of natural resource management in Idaho. Many of the proposed solutions are time and resource intensive, such as establishing boundary orga- nizations or structured knowledge networks. In this paper, we adopted a relatively inexpensive, efficient approach to enhancing the connection between science and end users through the use of an online survey of key informants in Idaho. McKenna and Main (2013) articulate the value of using key informants to obtain expert information related to a community’s needs; one recent example can be found in Berndtson et al. (2007), where researchers developed lists of potential study participants from staff recommendations, the literature, and snowball sampling to help identify grand challenges in public health.

An online survey was administered in February 2012 to evaluate which climate indicators were of primary concern to end users and which indicator datasets would be the most useful in their jobs (see the supplemental material, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/WCAS- D-13-00070.s1, for a copy of the survey). Using a pur- poseful (Coyne 1997) and snowball sampling approach (Creswell 2009), we obtained participant contact information from agency and organizational websites, and asked survey participants to provide contact information for other potential participants, or to forward the online survey directly to their colleagues. Ritchie et al. (2003) recommend purposive sampling as appropriate when the sample is intended to represent individuals who meet key selection criteria, and they note that this approach helps ensure that all key groups are included. We specifically sought individuals who would be in a position to comment on the utility of climate science to management or policy decisions. Additionally, our selection criteria were attentive to covering the full suite of professions (natural resource managers, specialists, and community leaders) that would ultimately use the final products of this indicator-based assessment in their work, in a form of maximum variation sampling (Sandelowski 1995). Thus, our sampling approach is most appropriately characterized as what Patton (1990) calls stratified purposeful sampling, designed to achieve coverage of all groups. A total of 612 individuals were asked to participate. Participants included individuals working for state agencies (37%), federal agencies (32%), nongovernmental organizations (21%), and other entities (8%, corporate or private, and local governments).

The Internet survey was developed online using Qualtrics software and followed a modified Dillman method (Dillman et al. 2009), where participants were invited to participate through a work e-mail address and two weeks later received a reminder e-mail. The survey format included sequential questions about 1) perceived importance of climate change impacts within the state with a focus on natural hazards and social change and 2) indicators of climate change most desired for assessment within five designated systems: water, forest, rangeland, agricultural, and social systems. The survey first asked participants about their personal concern regarding a broad range of climate impacts, and then asked about relevance of climate data to their jobs in an attempt to avoid an order effect, which could have caused participants to answer all questions with respect to their work interests and induce undesired priming (Salancik 1984). Within the first part of the survey, all respondents were asked to choose up to five impacts they were personally concerned about from a broad set of possibilities (see supplemental material). The specific options within this broad set were designed to be far reaching in scope, but may have inadvertently primed the participants to focus their future answers only within the constructs of the impact options provided. Next they were asked to choose up to three responses (of the 12 possible, with three additional open-ended options) regarding direct measures of climate (i.e., direct temperature and precipitation metrics) they found most relevant to their job. They were then asked to choose one of the five designated systems (i.e., water, forest, rangeland, agricultural, social) that was most relevant to their job. This choice took them to one of the five possible subpages (one per designated system) where they could choose the top three indicators of the 12 or more options within that system. They were then asked if another one of the five

designated systems was relevant to their job. If so, they were then directed to that designated system’s subpage to again choose their top three most relevant indicators. After two (at most) designated system subpages the participants were then directed to the conclusion of the survey. The decision to limit respondents to no more than two systems was based on a need to minimize the burden on respondents, as the lists of indicators were quite long and because—given the breadth of respondents—we recognized that not all systems would be primarily important to all respondents.

We developed the survey questions collaboratively as a research group, with each discipline represented (e.g., hydrology, ecology, etc.), generating a comprehensive list of climate measures, potential impacts, and indicators that were considered most salient to each system and reflected the focus of similar work in other regions (Pederson et al. 2010; Betts 2011; USGCRP 2011a,b, 2012).

Summary of survey findings

A total of 100 surveys were completed, with respondent demographics mirroring those in the total population surveyed (Fig. 2). The top four concerns regarding climate change impacts were water resource availability (16% of respondents), extreme drought (14%), changes in plant productivity (14%), and wildland fire (10%; Fig. 2). Regardless of participant sector, concerns about biophysical impacts were consistently rated as the highest importance, and concerns about recreation and transportation impacts were rated as the lowest importance.

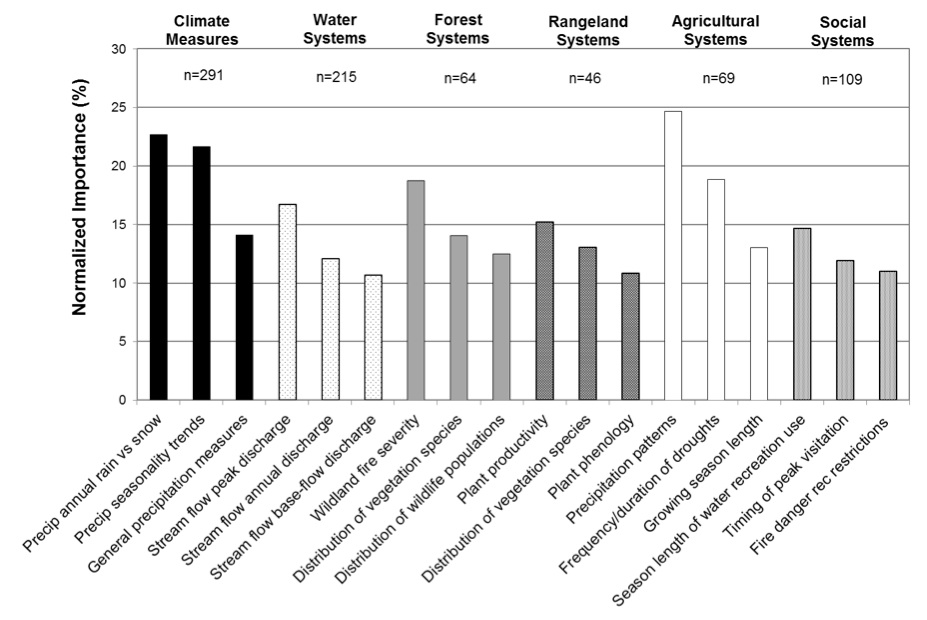

Based on a metric of ‘‘normalized importance,’’ which is defined as the number of times an indicator was selected by an individual end user divided by the total number of selections within a system, participants identified precipitation indicators as being the top three most useful climate measures: annual rainfall versus snowfall (23%), seasonality trends (22%), and general precipitation (14%; Fig. 3). Of all responses, 43% represented water-related occupational specialties as indicated by the choice of system specialties (Fig. 3). The top indicators for end users who selected the water resources system were streamflow timing, annual volumetric stream discharge, and stream baseflow discharge. Participants who selected the forest system focused on wildland fire severity and vegetation/wildlife distributions. Rangeland participants focused on vegetation indicators (i.e., plant productivity, vegetation distribution, and plant phenology). Agricultural participants focused on precipitation patterns, drought characteristics, and growing season length as their top priorities. Participants working with social systems selected water-based recreation, timing of peak visitation, and recreation restrictions due to wildland fire as the top climate change– related indicators.

Overall, participants were most concerned with water- related impacts resulting from climate change and considered information about water resources availability to be the most important measures of climate change that were relevant and useful for their needs (Fig. 2). The topics of fire and vegetation were also top areas of participant interest. The occurrence and impacts of wildland fire ranked fourth for participant concern (Fig. 2), and indicators related to fire were among the top four most relevant in forest, rangeland, and social systems (Fig. 3). The impact of climate change on plant productivity and growth rates ranked third for participant concern overall (Fig. 2).

FIG. 3. Climate change indicators that participants reported would be most useful within their work, pooled across all stakeholder types and segregated by natural resource system (top three per system are shown). ‘‘Normalized importance’’ is the number of times an indicator was selected by an individual end user divided by the total number of selections within a system.